Prostate cancer is the most common form of cancer among men in Germany. If it is recognized in time, and the tumour is still restricted to the prostate, the chances of recovery are good. However, as Prof. Axel Semjonow, Head of UKM’s Prostate Centre, explains, “The range of possibilities we have had so far for examining patients have not always delivered clear-cut findings.” He points out a new technology – so-called MRI/ultrasound fusion biopsy – which can help not only to provide a more precise image of any changes in the prostate, but also to carry out biopsies in a more targeted way.

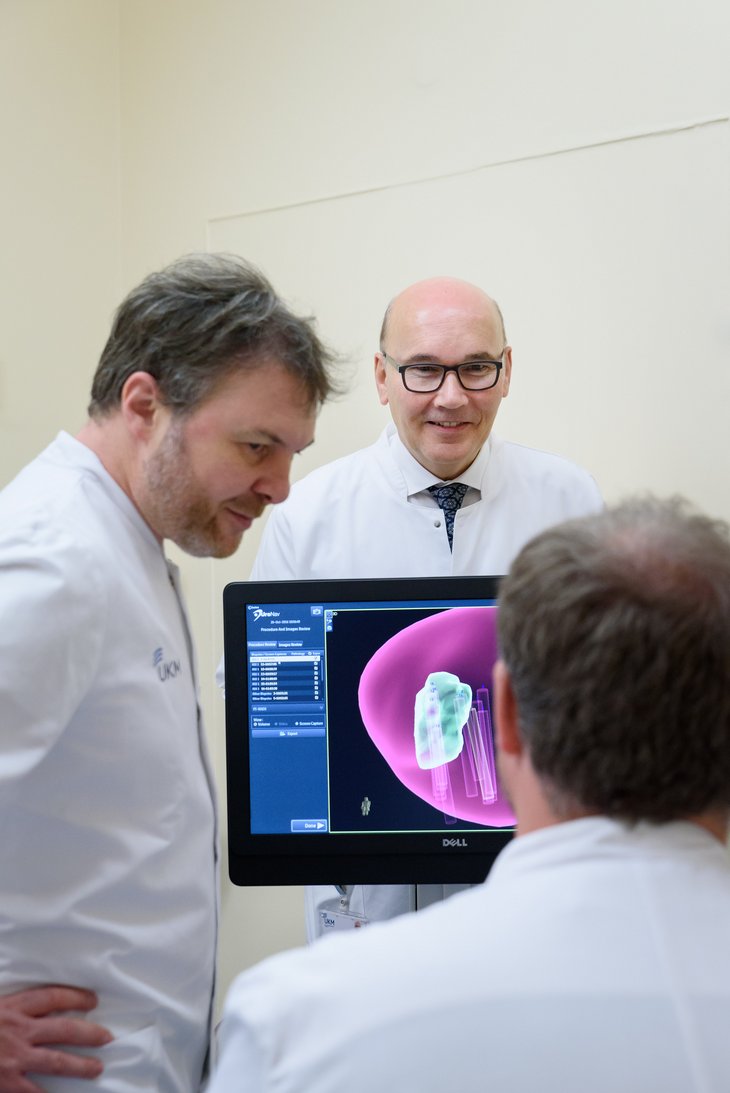

“The procedure is being used in just a few German hospitals,” says Prof. Walter Heindel, Director of Clinical Radiology at UKM. The images gained from preliminary examinations using MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) are combined in real time with ultrasound-guided biopsy images. “As a result, we can make a clear distinction between the prostate and any suspicious lesions. The position of the biopsy needle is also clearly visualized, Heindel explains.

The use of MRI as a preliminary examination is helpful if a prostate carcinoma is suspected but could not be be proven using traditional methods such as touch, ultrasound and a subsequent fan-shaped biopsy. “For example, if a man’s PSA level – a prostate-specific antigen which can help in the early detection of prostate cancer – is higher than usual, or even increasing, he is naturally going to be worried and will want to have some clear answers,” says Dr. Martin Bögemann, Head of the Urologic Oncology Section. “The physician treating him also needs a precise diagnosis as the basis for planning future therapies.”

Thanks to technical progress, the possibilities offered by so-called multimodal MRI as a preliminary examination are continually improving. “Multimodal” means that not only purely anatomical, but also tissue-specific, information is gathered. The use of higher field strengths through a much higher image resolution means that any malignant changes can be recognized at an early stage. Taken together, all the information provides a meaningful overall picture. If this information is then combined in the fusion biopsy with that provided by the ultrasound examination, samples of the suspicious tissue can be taken even in difficult areas. The risk of the biopsy needle not making the best possible contact with the tumour – or even of missing it entirely – is thus minimized. “The number of samples taken and of examination sessions are also expected to be reduced as a result of fusion biopsy,” says university teacher Dr. Thomas Allkemper, senior physician in the Department of Radiology.

A further advantage of the overall improvement in diagnostic possibilities is the fact that doctors can use the combined imaging to distinguish better between, on the one hand, lesions which only need to be carefully monitored and, on the other, aggressive types of tumour. In this way, excessive therapy can often be avoided. “Especially in the case of older patients with not very aggressive prostate cancer, it can take many years before any tumour-related complaints arise. For many of those affected, a non-aggressive tumour means neither any deterioration in their quality of life nor any shortening of their life expectancy,” says Semjonow. “What we offer these patients is so-called active monitoring.” The aim of this is to avoid any excessive therapy, in other words any unnecessary treatment. Some tumours progress faster, however, making prompt treatment necessary.

Radiologists and urologists are agreed that the new MRI/ultrasound fusion biopsy is a procedure which is not only easier on the patient and provides a more precise diagnosis in the case of a prostate carcinoma, but is also one which offers more certainty to the man involved, as well as to the doctor treating him. After all, the more information the imaging provides, the more individually the further steps or therapies can be adapted to needs.